Placental Accreta Spectrum (PAS)

Assoc. Prof. Pavit Sutchritpongsa

Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University

Placental Accreta Spectrum (PAS) is a condition in which the placenta abnormally attaches and grows too firmly into the wall of the uterus. In some cases, it grows so deeply that it is difficult to separate from the uterus after delivery, which can cause severe bleeding. This condition carries a high level of risk and can be dangerous for both the mother and the baby.

This condition occurs because the decidua basalis (the normal tissue layer that separates the placenta from the uterine muscle) is absent. As a result, parts of the placenta called placental villi (finger-like structures that help the placenta attach and exchange nutrients) can implant directly into the wall of the uterus and grow into the uterine muscle layer. This causes the placenta to attach much more firmly to the uterus than normal. The severity of PAS therefore depends on how deeply the placental villi invade the uterine muscle.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classifies the severity of Placental Accreta Spectrum (PAS) into three levels, as follows:

Placenta accreta (Grade 1)

The placental villi (finger-like structures of the placenta) grow through the decidua basalis but do not reach the uterine muscle layer (myometrium).

Placenta increta (Grade 2)

The placental villi grow into the uterine muscle layer (myometrium).

Placenta percreta (Grade 3)

The placental villi grow completely through the uterine muscle and reach the outer covering of the uterus (uterine serosa) or nearby organs, such as the bladder.

- Grade 3A: The placental villi reach the outer layer of the uterus (uterine serosa).

- Grade 3B: The placental villi extend into the bladder.

- Grade 3C: The placental villi extend into other organs, such as the intestines.

Conclusion: The Future of Healthcare

Risk Factors

- Having a previous cesarean section; the risk increases with multiple cesarean deliveries.

- Having a history of uterine surgery, such as surgery to remove uterine fibroids (myomectomy).

- Undergoing multiple uterine curettage procedures.

- Having a low-lying placenta (placenta previa).

- Having advanced maternal age.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

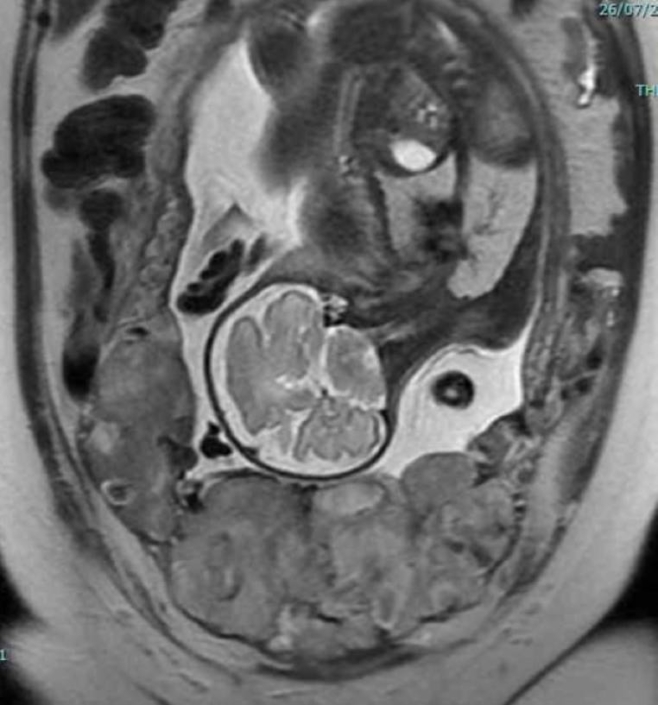

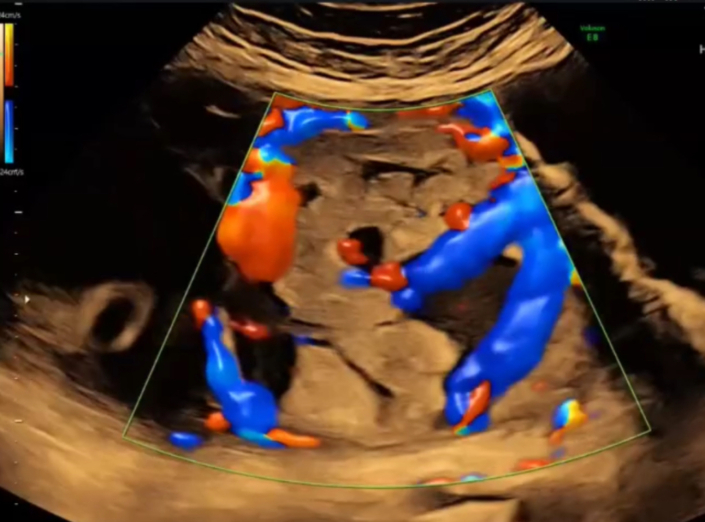

Most women do not have clear symptoms before delivery. However, doctors may suspect PAS based on a review of risk factors and examination using ultrasound (high-frequency sound waves). Typical findings may include the absence of the hypoechoic zone (a clear layer normally seen between the placenta and the uterus), the presence of lacunae (irregular blood-filled spaces) within the placenta, and the placental tissue extending beyond the normal uterine border.

In some cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to help assess the severity of the condition and how far the placenta has spread before planning treatment.

A key principle of care is preparation by a multidisciplinary team, which includes obstetricians, anesthesiologists, urologic surgeons, hematologists, and the blood bank.

The appropriate timing for delivery is usually a planned cesarean section. In general, delivery is recommended during the late preterm period, around 34 + 0 to 36 + 6 weeks of pregnancy. In more severe cases, delivery is often planned at 34 – 35 weeks of gestation.

The standard treatment is a cesarean section followed by removal of the uterus together with the placenta, known as cesarean hysterectomy with the placenta left in place (placenta in situ). This approach is used to prevent heavy bleeding.

In selected cases, conservative management, which aims to preserve the uterus, may be considered for women who wish to have more children. This option is usually limited to cases with lower severity and requires very close medical monitoring.

In the past, treatment of PAS was considered extremely complex and required extensive preparation. Interventional radiology procedures were often performed to block the uterine blood vessels, such as uterine artery embolization, before cesarean delivery. Patients usually needed postoperative care in the intensive care unit (ICU), large amounts of blood had to be reserved and transfused during surgery, and the risk of complications was high. These complications included severe postpartum bleeding, shock from blood loss, injury to the bladder or nearby organs, postpartum infection, and blood clots.

At present, the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology has established a dedicated multidisciplinary team to care for pregnant women with PAS. The team includes highly experienced surgeons and uses advanced techniques, such as bilateral internal iliac artery ligation (tying off the major arteries that supply blood to the uterus). Accurate diagnosis before delivery is achieved through detailed ultrasound and MRI examinations. With this approach, more than 100 cases of PAS have been successfully treated, with a low rate of complications. No maternal deaths have occurred, blood loss and blood transfusion rates have been low, and most patients have not required admission to the intensive care unit after surgery.

Conclusion

Placental Accreta Spectrum is a high-risk condition, often described as a nightmare that obstetricians hope never to encounter. However, maternal illness and death can be reduced when the condition is accurately diagnosed before delivery and when a planned cesarean section is performed by an experienced medical team in a hospital equipped with obstetric surgery, diagnostic imaging, and hematology services.